![]() Home Transit

of Venus Sewer History in Leeds Sundials

in Leeds William Gascoigne John Feild About

Home Transit

of Venus Sewer History in Leeds Sundials

in Leeds William Gascoigne John Feild About

![]() Serendipity and a Spider

Serendipity and a Spider

William Gascoigne

(c.1612-44) and the Invention of the Telescope Micrometer

As the French astronomer Adrien Auzout penned a letter to the Royal Society of London on 28th

December 1666 he could not have imagined the consternation that it would cause.

Nor could he have guessed that his action would almost certainly save from

oblivion the work of a young astronomer from northern England, who had suffered

a violent death almost a quarter of a century earlier.

Full of enthusiasm, Auzout wanted to

tell English scientific friends of his invention of the telescope micrometer:

an entirely novel device that, together with Jean Picard, he had used to

measure the angular diameter of the Sun, Moon and planets. “We can take

diameters to seconds”, he wrote, “…. and we can be almost certain that we

cannot be mistaken by more than 3 or 4 seconds …. I can well assure you that

the diameter of the sun was hardly smaller at its apogee than 31' 37" or

40"”

When Richard Towneley, a wealthy

Lancashire patron of science, saw Auzout’s letter in

the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, he was dismayed. He

contacted the Society: “I am told I shall be looked upon as a great wronger of our Nation, should I not let the World know,

that I have out of some scattered Papers and Letters that formerly came to my

hands, of a Gentleman of these parts, one Mr Gascoigne, found out, that before

the late unfortunate wars, he had not only devised an Instrument of as great a

power as Monsieur Auzout’s, but had also for some

years made use of it …. The very Instrument he first made, I have now by me”.

Towneley’s letter

appeared in the next issue of the Transactions. Auzout,

though keen to have more details, took the news with good grace.

Towneley’s letter

appeared in the next issue of the Transactions. Auzout,

though keen to have more details, took the news with good grace.

Of the life of William Gascoigne (1612-44), the Yorkshire

astronomer whose micrometer and observations had fallen into the hands of Towneley, little was known. He was born into a wealthy

land-owning family and lived at New Hall in the tiny Yorkshire village of

Middleton, near Leeds. He made his own lenses and telescopes, and invented a

telescopic sight and a telescope micrometer. Before his untimely demise, he had

a Treatise on Optics ready for the press.

Though by his own account spending on astronomy only the same time

as friends and neighbours spent on “hawks and hounds”, by the age of 28

Gascoigne had made some remarkable innovations. He had devised experiments to

show how an inverted image was cast onto the retina of the eye. He had verified

the sine law of refraction – recently published by Descartes – and had used the

same law to calculate the angular size of the Sun, from the size of its image

projected by a Galilean telescope.

One day, returning to the open case of a Keplerian

telescope with which he had been experimenting, Gascoigne found that a spider

had spun its web inside the case – a few centimetres from the convex eyepiece.

With characteristic curiosity, rather than sweep the web aside, he bent to look

through the telescope. To his astonishment, he saw that, not only was the web

in focus, so too were distant objects.

“This is that admirable secret, which, as all other things,

appeared when it pleased the All Disposer, at whose direction a spider’s line

drawn in an opened case could first give me by its perfect apparition, when I

was with two convexes trying experiments about the sun, the unexpected

knowledge.”

In the Keplerian telescope the objective lens was convex and

unlike in the Galilean model so too was the eyepiece lens. With this

arrangement any object placed at the focal point of the objective lens, could

be magnified and brought into focus alongside the image of the distant object

being viewed. This ‘incredible rarity’, as Gascoigne called it, immediately

suggested a number of possibilities. Firstly, it was feasible to introduce a

simple marker, to act as a telescopic sight.

“if

I .... placed a thread where that glass [the eyepiece]

would best discern it, and then joining both glasses, and fitting their

distance for any object, I should see this at any part that I did direct it to ...”

Secondly, one could

introduce a measuring device into the common focal point and thereby measure

the size of the observed image. At first he used simply a scale. Then he

introduced a pair of brass pointers. These were mounted on a screw and could be

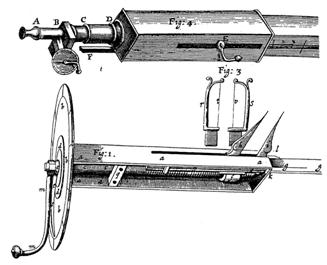

moved towards and away from each other by turning the screw (Fig.1). The change

in separation was proportionate to the number of turns, as also was the angular

separation of the two distinct points enclosed by the pointers. With this

ingenious device he measured the diameters of the sun, moon and planets.

Fig.1

Gascoigne's telescope

micrometer

Gascoigne was in regular contact with the young Lancashire

astronomers, William Crabtree and Jeremiah Horrocks

and, for a remarkable, though lamentably brief period, these three blazed a

trail for precision astronomy in Europe.

Whilst William Crabtree, however, was using something similar to a

cross-staff, fitted with needles, to observe the sun through thin cloud and

measure its angular diameter, Gascoigne, by contrast, was using the “wheels and

screws” of the micrometer to make similar measurements with unprecedented

accuracy. The whole purpose was to test Kepler’s idea

that shape of the Earth’s orbit was an ellipse, rather than the eccentric

circle argued by Copernicus.

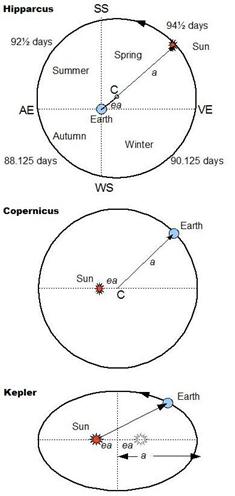

From ancient times it had been assumed by astronomers that the

distance between the Earth and the Sun varied over the course of the year

(Fig.2). Hipparchus had deduced this

from the observed difference in the length of the seasons and an assumption

that the Sun moved around the Earth at a uniform speed. Copernicus, though he placed the Earth in circular motion around

the Sun, was obliged to offset the centre of the circle from the Sun to get the

right length for the seasons. Kepler introduced

the notion of an elliptical orbit of the Earth, with the Sun at one focus of

the ellipse. All these theories implied a variation in the apparent angular

diameter of the Sun throughout the year. The variation of this apparent

diameter and hence the ‘eccentricity’ of the orbit, however, was far too slight

to be measured reliably - until, that is, the invention of the telescope

micrometer. Herein lay the importance of the device invented by Gascoigne and Auzout. The precise value of the eccentricity could be

calculated from the semidiameters at the furthest and

nearest approach of the Earth to the Sun. What is more, they would differ,

according to whether Copernicus or Kepler was

correct.

Fig.2 Three alternative models for the orbital

eccentricity in the Earth-Sun system.

a=maximum distance

of the orbiting body from the centre of the of orbit

e= the eccentricity.

The offset of the Earth (geocentric theory) or the Sun (heliocentric theory)

from the centre of the orbit, expressed as a fraction of a

SS= summer solstice, WS=winter solstice, AE=autumnal equinox, VE=vernal

(or, spring) equinox

Gascoigne’s values of 15' 53" and 16' 25", respectively,

implied an orbital eccentricity of 0.01651 (compared with the current value of

0.01672), and helped to confirm the elliptical orbit of Kepler.

In 1642 England was plunged into a bloody civil war, which brought

an end to Gascoigne’s astronomical pursuits. We will perhaps never know what

impelled William Gascoigne to join the King’s side in the conflict. Whatever

the case may have been, he abandoned his telescopes and – despite the

impediment of a lame leg - threw in his lot with the Cavalier army of Charles

I.

Within two years he was dead - killed by a bullet, according to

Christopher Towneley, at the battle of Marston Moor

near York on 2nd July 1644: His naked body probably thrown into a

mass burial pit along with up to 10,000 other unfortunate young men.

RESCUED

FROM OBLIVION

Even after Richard Towneley’s belated

account of Gascoigne’s inventions it appeared that his contributions

were destined to fade into oblivion. A

handful of letters between Gascoigne and Crabtree were in the hands of the Towneley family, until 1711 when they were handed to the

Reverend William Derham.

Shortly after getting them, Derham

happened to notice an obscure passage in the Preface to 1687 tables of Philippe

de La Hire (1640-1718), in which the invention of the telescopic sight was

attributed to Picard. Derham promptly wrote to the

Royal Society in London, saying “Monsieur de La Hire … robs our Mr Gascoigne of

the honour of first applying telescopic sights to mathematical instruments and

ascribes it to Monsr Picard …. Now since Mr

Gascoigne’s papers are in my hands … I am fully able to do Mr Gascoigne

justice”.

When Derham’s paper was published, it

demonstrated beyond doubt, with extracts from letters of Gascoigne and

Crabtree, that Gascoigne had not only invented the telescopic sight and

micrometer, but had also taken many measurements with them.

Meanwhile,

de la Hire was busy compounding his ‘misdemeanour’. In a new memoir concerning

the date of the invention of the Micrometer he did not even mention Gascoigne.

Instead, he said “we are indebted to Monsieur Huygens for the invention of the

micrometer”.

Across

the Channel it took nearly four decades for a response to come. By then John

Bevis – the discoverer of the Crab Nebula – had found a new piece of evidence

confirming Gascoigne’s achievements. In the library of the Earl of Macclesfield

he had found and copied a letter written by Gascoigne to the mathematician,

William Oughtred, in 1640-01. “It consists of several

sheets of paper”, he reported to the Royal Society, “all about his invention

for measuring small angles to seconds; where he not only gives the geometrical

and optical principles of his contrivance, and the construction of the

instrument, but also a series of observations actually taken therewith.”

Eventually, the true role of Gascoigne was acknowledged on both

sides of the Channel. In his authoritative History

of Modern Astronomy (1821) the French astronomer, Jean-Baptiste

Delambre devoted several pages to Gascoigne and the

priority dispute. He acknowledged the Middleton astronomer’s micrometer

measurements of the solar disc and compared them favourably with the

theoretical values given in the French national almanac, Connaissance des Temps.

Gascoigne Connaissance

des Temps

25 October (OS) 16' 11" or 10" 16' 10"

31

October 16'

10" 16'

11".4

2

December 16'

24" 16'

16".8

Horrocks and Crabtree achieved lasting fame

because of their observation of the 1639 transit of Venus. A fame which is

reinforced with each fresh transit ‘season’, including that through which we

are fortunate to have lived (2004-12). Their friend, William Gascoigne –

according to Flamsteed, “as ingenious a person as the

world has bred or known” - has been consigned, however, to a mere footnote in

the history of astronomy.

The original letters that Derham

acquired have long since been lost. Ironically, it is largely due to the

unintentional ignoring of Gascoigne’s achievements by French astronomers (Auzout, de La Hire) that Gascoigne was rescued from total

oblivion. Without the resulting priority dispute, we would

probably be unaware of the tragic story of that remarkable young man.

*******************************************************************

Note: David Sellers is the author of The Transit of Venus: the Quest to Find the True Distance of the Sun

(Leeds, 2001), co-author of Vénus devant le Soleil (Paris, 2003, Ed. A Simaan), and the author of In Search of William Gascoigne: Seventeenth Century Astronomer

(Springer, New York, 2012)

FURTHER READING

Sellers, David, In Search of William Gascoigne: Seventeenth Century Astronomer, Astrophysics and Space Science Library, Volume 390. ISBN 978-1-4614-4096-3. Springer Science+Business Media New York (2012) - see publisher's flyer

Sellers, David, A letter from William Gascoigne to Sir Kenelm Digby, Journal for the History of Astronomy (ISSN 0021-8286), Vol. 37, Part 4, No. 129, p. 405 - 416 (2006)

Chapman, Allen, Three north country astronomers (1982), Dividing the Circle (pp. 35-45) (1995), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (pp. 591-3) (2004)

Willmoth, Frances, William Gascoigne, in Encyclopedia of the Scientific Revolution (ed. Wilbur Applebaum) (2000)

Thoren, Victor, William Gascoigne, in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (ed. C.Gillespie) (1972)

Taylor, R.V., Biographia Leodiensis (pp.86-7) (1865)

Wheater, William, William Gascoigne - the astronomer, The Gentleman's Magazine (pp.760-762) (1863)